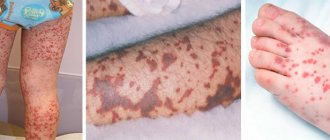

Lyell's syndrome is an inflammatory-allergic pathology characterized by a severe course and related to bullous dermatitis. This is a drug-induced toxic damage to the body, manifested by general and local symptoms. Systemic disorders include dehydration, dysfunction of internal organs, and the addition of a bacterial infection. Local damage is the appearance of characteristic morphological elements on the skin and mucous membranes: blisters, erosions, scars. Lyell's syndrome according to ICD-10 has code L51.2 and the name “Toxic epidermal necrolysis”.

The pathology was first described in 1956 by a dermatologist from Scotland, Alan Lyell, in whose honor the syndrome got its name. In his scientific works, he wrote that a severe form of toxicoderma is a special reaction to drugs - antibiotics, sulfonamides, NSAIDs . It has now been proven that this syndrome refers to drug allergic reactions and is considered the same severe pathological condition as anaphylactic shock.

Lyell's syndrome has several equivalent names - toxic epidermal necrolysis, bullous drug disease, burn skin syndrome, malignant pemphigus. These terms essentially refer to the same disease, manifested by the formation of blisters on the skin, as in a burn disease. Lyell's syndrome usually develops in children with weak immune defenses and older people with a number of chronic diseases. Most often it is observed in the male half of the population. Clinical signs of the disease appear a couple of hours after the administration of a certain medication.

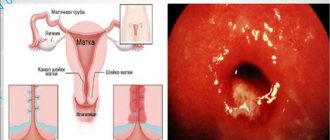

Of all allergopathologies, Lyell's syndrome has the most severe outcome. Necrotic damage to the epidermis and its detachment are caused by the toxic effect of allergens on the patient's body. Blisters, erosions and scars appear on the skin of the abdomen, shoulder girdle, chest, buttocks, and back. The mucous membranes of the oral cavity, larynx, and genitals are most susceptible to damage. Acute inflammation of the visceral skin zone manifests itself with characteristic clinical signs, often life-threatening.

Diagnosis of Lyell's syndrome is:

- conducting a thorough examination of the patient,

- monitoring coagulogram data,

- studying the results of laboratory tests of blood and urine.

Characteristic changes in the condition of the skin allow a correct, often fatal, diagnosis to be made in time. Treatment of the pathology is complex and multicomponent. Patients undergo extracorporeal blood purification, infusion, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and dehydration therapy. To save the life of the patient and prevent serious consequences of the disease, prompt medical intervention is required.

From the history of the syndrome

This pathology was first described in 1956 by Scottish dermatologist Alan Lyell. He systematized 11 reports of 14 cases of this disease, 4 of which he personally observed.

Lyell replaced the previously accepted designation “acute pemphigus” with “toxic epidermal necrolysis” (TEN). The fact is that in all patients o. The rash served as the main diagnostic sign for identifying a new nosological unit. Lyell coined the term “toxic” because he believed that the disease was caused by toxemia, a specific toxin circulating in the body. “Necrolysis” is a medical neologism invented by Lyell himself, who combined in it the main clinical sign - “epidermolysis” and the histopathological sign - “necrosis”.

Lyell also noted the severity of damage to the mucous membranes and the unusual weakness of inflammatory processes in the dermis - “dermal silence.”

In the scientific world, the disease received the name of its discoverer during Lyell’s lifetime - in the 60s. However, the dermatologist himself always used the designation TEN.

In 1967, after conducting a targeted survey of colleagues throughout the UK, Lyell presented the most extensive summary of TEN to date - 128 cases of the disease. In the same year, he described 4 forms of TEN, corresponding to a specific etiology: staphylococcal, drug, mixed and idiopathic.

“Necrolysis” is a medical neologism invented by Lyell himself, who combined in it the main clinical sign - “epidermolysis” and the histopathological sign - “necrosis”.

Currently, the staphylococcal form of Lyell's syndrome is identified as a separate nosological unit: staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS, L00 according to ICD-10).

Prognosis of toxic epidermal necrolysis

The prognosis largely depends on the stage of development of toxic epidermal necrolysis at which complex treatment was started. If therapy was carried out immediately when the first symptoms appeared, the progression of the pathological process can be stopped within a week. After this time, the patient fully recovers.

When Lyell's syndrome progresses rapidly and therapy is not carried out on time, the prognosis is unfavorable. Even death is possible.

Lyell's syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis is a dangerous disease of an allergic nature that can occur in a fulminant form. That is why it is necessary, when the first signs of its progression appear, to contact a medical institution for help or call an ambulance. Folk remedies for the treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis should not be used so as not to worsen your condition.

You can watch the video about the disease:

Epidemiology

Since the 70s, medicine has kept an annual record of the prevalence of Lyell's syndrome. According to various authors, rates range from 0.4–1.3 cases per 1 million population per year. Mortality rates range from 20–60% of the number of cases, depending on the state of the region's health care system. Thus, the number of deaths from this pathology throughout the world per year is in the thousands. Among immediate allergic reactions, Lyell's syndrome is second only to anaphylactic shock in terms of mortality. In the general structure of drug allergies, the share of Lyell's syndrome is 0.3%. Women are more often affected: the ratio to male patients is 1.5:1. There was no direct relationship between the risk of the disease and age. Patients who have previously had Lyell's syndrome, especially in childhood, are considered a risk group.

The most common form of the syndrome is medicinal, up to 80% of all cases. After medicinal, the second most common cause is malignant neoplasms (especially lymphomas). The frequency of idiopathic cases of the syndrome is 5–10%.

In children, Lyell's syndrome more often - up to 60% of cases - has an infectious etiology. A special risk group for the manifestation of the disease among children is those who suffered from acute respiratory viral infections at an early age and underwent a course of treatment with NSAIDs in connection with this.

Prevention methods

There is no specific prevention yet, the disease itself has not been fully studied, and all the factors that can trigger the onset of a complex systemic allergic reaction are unknown. Experts advise everyone, without exception, to take medications only as prescribed, strictly follow the prescribed dosages, and each time inform your doctor about adverse reactions that occur as a result of the medications used. You cannot take more than five different drugs at the same time. Self-medication of people who are predisposed to allergies is considered unacceptable.

Etiology

Discussions about the etiology and pathogenesis of Lyell's syndrome continue. The most studied drug form of the disease, which develops due to a violation of the body’s ability to neutralize reactive intermediate drug metabolites. These metabolites interact with tissues, resulting in the formation of an antigenic complex, the immune response to which initiates the development of the disease.

In fact, a genetic predisposition to this pathology has also been proven, in particular in individuals with a number of HLA histological compatibility complex antigens: A2, A29, B12, B27, DR7. The presence of chronic foci of infection in the body (sinusitis, tonsillitis, cholecystitis, etc.), leading to decreased immunity, increases the risk of disease. HIV-infected patients are a special risk group: their risk of developing Lyell's syndrome is 1000 times higher than in the general population.

Factors contributing to the development of the disease

The main factor contributing to the appearance of Lyell's syndrome is the intolerance of patients to certain types of drugs in the treatment of diseases.

The most dangerous drugs include sulfonamides (Biseptol, Sulfodimethoxine, Streptocide, Sulfasalazine and Sulfalene). In addition, the following groups of drugs can lead to the development of the syndrome:

- antibacterial drugs (penicillin, tetracycline and macrolides) and especially Erythromycin;

- anticonvulsants (Phenobarbital, Phenytoin);

- anti-inflammatory and painkillers (Aspirin, Diclofenac, Analgin);

- antituberculosis (isoniazid);

- vitamins and contrast agents for radiography;

- Dietary supplements and immunotherapy drugs.

One of the probable factors in the occurrence of Lyell's syndrome is an acute infectious process caused by staphylococcus. In addition, cases have been described where the causes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome have not been clarified, i.e. in the complete absence of provoking factors (infection, medications, etc.), the pathological process nevertheless progressed.

Diagnostics

For differential and laboratory diagnosis, provocative tests are not performed, since the risk of uncontrolled complications is high. The most common are extraorganismal diagnostic tests based on the reactions of the patient’s blood cells to a substance that has sensitized the body. These include: the Shelley basophil degranulation test, the Fleck leukocyte agglomeration test, the blast transformation reaction of lymphocytes, hemolytic tests.

HIV-infected patients are 1000 times more likely to develop Lyell's syndrome than the general population.

Apoptosis of keratinocytes is one of the first tissue morphological signs of Lyell's syndrome. Needle biopsy using frozen skin sections is becoming increasingly common. This reveals the absence of typical acantholytic cells, total epidermal necrolysis, sub- and intraepidermal blisters.

First aid

If symptoms are detected, you should:

- Stop taking medications that contain substances that may be allergens;

- Remove the elements remaining in the body using enemas, diuretics and laxatives;

- Hospitalize the child. Most likely, the small patient will be treated as a burn patient (the skin condition is similar to second or third degree burns).

Flow

Based on the nature of the course, there are three variants of the clinical picture of Lyell’s syndrome:

- Fulminant form - up to 10% of all cases. Develops over several hours. Etiology: idiopathic or drug-induced. Skin lesions cover up to 90% of the body surface per day. Impaired consciousness up to coma. Acute renal failure - anuria. Due to the fact that most of these patients do not survive to hospitalization or are admitted in a terminal condition, the fatal outcome is 95% within 2–3 days. At autopsy, the internal organs are usually intact.

- Acute form - 50–60% of cases. Damage to the skin and mucous membranes goes through the entire spectrum of maturation: from rashes to necrolysis. The area of necrolyzed surfaces can reach 70% of the body surface. The disease lasts from 7 to 20 days. Starting from 3–4 days, symptoms of renal, hepatic, cardiovascular, and pulmonary failure appear, as well as infectious complications—primarily pulmonary and genitourinary system infections—and as the disease progresses, sepsis. Mortality reaches 60%.

- Favorable course (smoothed form) - frequency up to 30% of cases. Damage to the skin and mucous membranes does not exceed 50% of the body surface. Clinical manifestations reach their peak on days 5–6 of the disease. Then, within 3–6 weeks, the patient’s condition improves until full health is restored.

The overwhelming majority of patients - more than 90% - have erosive changes in the mucous membranes. Typical complaints are pain along the urethra during urination and photophobia.

A positive Nikolsky symptom is characteristic: detachment of the epidermis on externally unchanged skin with sliding pressure and detachment of the peri-vesical epidermis when pulling on a piece of the vesical tire. In especially severe forms, total detachment of the epidermis is observed due to friction over the entire surface of the patient’s body.

Forms and types of disease

Experts, taking into account the different etiologies of the pathology, have identified the following forms of the disease:

- The drug develops as a result of drug exposure.

- Staphylogenic occurs as a complication of a bacterial infection. This form develops only in children. It does not depend on the use of drugs and is not fatal. The prognosis for such a diagnosis is always favorable.

- Idiopathic form. It includes all cases in which it is not possible to identify the trigger points of the disease.

- A form that occurs with secondary pathologies. This group includes those episodes in which Lyell's syndrome develops against the background of psoriasis, chickenpox, herpes zoster or pemphigus.

The acute course of any form has the same clinical picture.

Stephen-Johnson syndrome or Lyell's syndrome?

One of the main prognostic factors for Lyell's syndrome is the area of the necrolyzed surface. Therefore, a correct assessment of its length is very important. For this, the same rules are used as in combustiology: the rule of “nine” - when the arms, chest and stomach are considered to be 9% of the body surface, and the back and legs are 18% each; and the “one percent palm” rule. For a more accurate assessment, it is recommended to measure the area of the separated and separated epidermis not only in areas with pronounced erythematous changes, but also in areas of the body remote from the “epicenter”. Depending on the area of the surface affected by necrolysis, clinical differences between Lyell’s syndrome and Stephen-Johnson syndrome are distinguished.

For 30 years - since the late 70s - corticosteroids were considered an essential part in the treatment of Lyell's syndrome. In recent years, criticism has emerged regarding their effectiveness: in particular, it is indicated that their use increases the risk of septic complications.

In recent years, the theory has been gaining popularity that these syndromes are two variants of the severe outcome of an epidermolytic skin reaction to medications and differ only in the degree of skin detachment.

General rules of treatment

How to get rid of dangerous symptoms if they are caused by medications?

Therapy is divided into two types:

- specific treatment methods. Identification and exclusion of medications, the “culprit” of unpleasant manifestations;

- nonspecific treatment methods. During treatment and preventive measures, all stages of various types of allergic reactions are affected.

Procedure:

- Analyze which drug led to negative consequences. For acute reactions this is easy to do, but for protracted reactions it is more difficult. It will require interaction between the doctor and the patient, analysis of events preceding allergic reactions;

- at the first signs of an allergy, stop taking medications if you have not eaten hazardous foods, petted cats, dogs, breathed pollen, or been bitten by insects;

- Unbutton the victim’s clothes, open a window or window for fresh air;

- in case of pronounced symptoms, attacks of suffocation, wheezing, severe swelling of the body, face, mucous membranes, immediately call an ambulance;

- Visit an allergist as soon as possible. You cannot do without a visit if you are using medications to treat serious pathologies;

- take antihistamines. Products from this group should be in any first aid kit, regardless of whether you suffer from allergies or not;

- it is desirable to have drugs of the latest generations that do not cause drowsiness and contain a minimum dose of the active substance;

- recommended Loratidine, Terfenadine, Cetirizine, Telfast, familiar to everyone Suprastin, Diazolin, Cetrin, Tavegil;

- drink enough liquid, preferably purified or table (non-medicinal) mineral water;

- take any sorbent that you find at home - activated or White carbon, Enterosgel, Polysorb;

- Calcium chloride, cocarboxylase, Diphenhydramine in injections are recommended.

How to treat herpes zoster on the body? We have the answer!

The best folk remedies for foot fungus are described at this address.

Follow the link and read an interesting article about how and how to treat fungus on your hands.

Systemic therapy

Unfortunately, there are no uniform clinical recommendations for diagnosed Lyell's syndrome. This is primarily due to the multi-organ nature of the lesions, which presupposes, first of all, multidirectional symptom-based therapy. For the treatment of Lyell's syndrome, the rule of “cancelling the last” prescribed medication is most often ineffective, since the time of manifestation of the disease varies from several hours to several days. Therefore, it is recommended to discontinue all previously prescribed medications and emergency symptomatic therapy. It has been confirmed that quick and total withdrawal of all medications when it is impossible to clearly identify a specific allergen improves the prognosis of the disease by 30%. As part of the specific treatment of allergic Lyell's syndrome, most researchers clearly recommend:

- emergency, preferably in the first hours of the disease, cascade plasma filtration (plasmapheresis), which allows removing up to 80% of the patient’s plasma. If plasmapheresis is technically impossible, hemosorption is recommended;

- massive systemic corticosteroid therapy. Recommended corticosteroid regimens range from 3–4 mg/kg body weight on the first day of illness to complete prohibition as the patient’s condition worsens;

- intravenous immunoglobulins. The daily dose, starting from the first day of the disease, varies from 0.2 to 0.75 g/kg of the patient’s body weight. The duration of the cycle is from 4 to 12 days. The effectiveness of immunoglobulins is due to the content of natural anti-Fas antibodies that regulate apoptosis and proliferation in intact and transformed lymphoid cells. They reduce the incidence of bacterial complications and prevent progression of the syndrome;

- hyperbaric oxygenation in the absence of abscesses, cavities and free airway patency in the patient’s lungs.

Treatment of lesions of the skin and mucous membranes is carried out according to the principles of burn therapy. The parenteral nutrition regimen is observed. Correction of infusions is carried out depending on the patient's condition.

During the period of hospitalization, regular - at least once every 72 hours - examinations by a urologist, ophthalmologist, dentist, or otolaryngologist are required in order to promptly identify and prescribe appropriate therapy for damage to the mucous membranes.

Causes

The syndrome occurs when:

- Drug overdose, both one-time and long-term. Therefore, you should always take tablets, syrups, tinctures after reading the instructions on the package!

- Treatment with medications to which the patient is allergic;

- Treatment against the background of reduced immunity. The most common cases are during the period of exacerbation of infections (primarily HIV), herpes virus, Einstein-Barr virus, citalomegavirus, after brain and internal organ transplant surgery, radiation therapy to cure cancer;

- A reaction with a cause unknown to modern science.

The greatest risk of getting sick is with an overdose of the following elements (drugs are indicated in parentheses):

- Sulfonamides (“Etazol”, “Urosulfan”);

- Allopurinol (“Allopurinol-Egi”, “Allupol”, “Purinol”);

- Phenytoin (“Difenin”, “Alepsin”), mephenytoin (“Mesantoin”), fosphenytoin;

- Phenylbutazone (“Butadione”, “Phenylbutazone”);

- Carbamazepine (“Finlepsin”, “Tegretol”, “Zeptol”, “Mazepin”);

- Piroxicam (“Remoxicam”, “Felden”);

- Chlormesanone;

- Thioacetazone;

- Amminopenicillin;

- Salicylic acid.

Forecast

Since 2011, the SCORTEN scale for assessing the severity of Lyell's syndrome has been widely used in the West. It takes into account the following prognostic factors:

- patient age > 40 years;

- Heart rate > 120 beats. in min.;

- presence of concomitant malignant oncological disease;

- affected body surface area > 10%;

- blood urea level > 10 mmol/l;

- plasma bicarbonate level

- blood glucose > 14 mmol/l.

The presence of each factor increases the risk of death. Thus, the approximate risk of death is: in the presence of 1 factor - up to 3.2%; 2 factors - 12.1%; 3 factors - 35.3%; 4 factors - 58.3%; 5 or more factors – 90%.

Clinical case

In 2009, in Donetsk, I witnessed a rare case for Donbass (only 6 cases in the Donetsk region from 1991 to 2013!) case of Lyell's syndrome.

Patient: 37 years old. Allergic and infectious anamnesis are not burdened. Three days before admission, she fell ill with a cold. She was treated with “familiar” medications: cough tablets, eye drops, nasal drops, vitamins. From the evening of the second day, itching and rashes appeared. She took suprastin on her own. After short-term relief, the condition worsened. In the evening on the third day, after fainting, she was taken to the city hospital by emergency medical services, and within a few hours was transferred to a regional clinic. A woman was admitted with hyperemic skin on her chest, shoulders, and inner thighs. On the third day, bubbles filled with cloudy contents appeared. The volume of others reached 100 ml. Throughout the entire period, hyperemia of the eyelids, sclera, mucous membranes of the oral cavity, and perianal area persisted.

From the third day, the combustiologist made repeated attempts to close the wound surface of the xenoskin. However, short-term periods of calm were replaced by psychomotor agitation in the patient, which led to displacement of the bandages and xenoskin. Not a single flap took root. Over the course of two weeks in the intensive care unit, the patient spent more than half of the time in forced medicated sleep. And from the sixth day, when the patient’s condition became critical, she was transferred to permanent mechanical ventilation.

In this case, Lyell's syndrome was diagnosed within two days after the patient was admitted to the hospital; the course of the disease was not lightning fast, but rather acute; Asymptomatic therapy was carried out, but it was not possible to save the woman.

Therapeutic measures

Patients with Lyell's syndrome are urgently hospitalized in the intensive care unit of a burn hospital. Timely provision of medical care helps save the patient’s life. General therapeutic measures include detoxification and treatment of lesions on the skin. Treatment is aimed at normalizing water and salt balance, restoring blood supply to internal organs and their functions.

At the prehospital stage of medical care, it is necessary to stop taking the drug that caused the disease, rinse the stomach, and give a cleansing enema. Patients should drink plenty of fluids. Antihistamines are administered parenterally - Suprastin, Pipolfen, Diphenhydramine.

Inpatient treatment includes:

- To combat dehydration and normalize the water-salt balance, constant infusion therapy is carried out under the control of daily diuresis. Saline solution, dextran, rheopolyglucin, hemodez, plasma or albumin, and Ringer's solution are injected intravenously.

- The blood is purified by plasmapheresis or hemosorption; patients are prescribed corticosteroids and antibiotics in large doses.

- Symptomatic treatment consists of the use of drugs that support liver function - Phosphogliv, Essentiale Forte, Karsil.

- Patients are prescribed proteolysis inhibitors – “Gordox”, “Kontrikal”.

- They use drugs that reduce blood clotting - Curantil, Persantine, Dipyridamole.

- Diuretics - Furosemide, Mannitol, Veroshpiron.

- Immune therapy using immunomodulators – “Ismigen”, “Licopid”.

- Wound healing ointments are used locally - Solcoseryl, Bepanten, Levomekol, special aerosols and solutions for rinsing the mouth. Since Lyell's syndrome is characterized by severe pain, local therapy is carried out after pain relief. Dressings are often performed on patients under general anesthesia.

- Patients with this syndrome require special care, including the use of sterile cotton-gauze dressings and linen. All wards must be equipped with germicidal lamps. They need to maintain optimal humidity and air temperature. Such conditions prevent the penetration of infection from the external environment.

At home, after discharge from the hospital, treatment with small doses of corticosteroids is continued with gradual withdrawal of the drug. The lesions are treated with aerosols or wet dressings containing glucocorticosteroids, and lotions with antibiotics are made.

For the treatment of pathology, folk remedies and herbal remedies are practically not used. You can rinse your mouth with a decoction of sage or chamomile, lubricate the lesions with beaten egg whites, or treat them with vitamin A.