What is toxic shock syndrome?

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is a rare, life-threatening bacterial infection. The syndrome occurs when the bacteria responsible—Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes, which normally live harmlessly on the skin—enter the body's bloodstream and release toxic toxins.

These toxins cause a significant decrease in blood pressure (shock), leading to dizziness and confusion. They also damage tissue, including skin and organs, and can interfere with many vital organ functions. If toxic shock syndrome is not treated, the combination of shock and organ damage can lead to death.

How common is TSS?

Anyone can experience toxic shock syndrome—men, women, and children. For reasons still unclear, a significant proportion of cases occur in menstruating women who use tampons, especially tampons designed to be “super absorbent.”

TSS can also occur as a result of an infected abscess, insect bite, or wound, for example. Some cases involve damage to the skin from a burn, which allows bacteria to enter the body and release toxins.

The risk of toxic shock syndrome is higher in younger people. This is thought to be because many adults and older people have developed immunity (resistance) to the toxins produced by the bacteria.

TSS is an extremely rare condition, with approximately 3-5 in 100,000 people developing the syndrome each year. Two or three of them will die.

If toxic shock syndrome is diagnosed and treated early with antibiotics, there is a good chance of recovery.

Pathogenesis

Infectious-toxic shock of any etiology triggers a generalized reaction of the body. In response to the release of toxins by bacteria, the immune system turns on defense mechanisms.

Scientists call this process a mediator storm. Hormones and biologically active substances are released into the bloodstream in large quantities. They affect blood vessels and the permeability of their walls. But the reaction extends beyond the boundaries of one organ or system. This is the main danger of infectious-toxic shock.

The blood supply to the brain, heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract deteriorates. The process is called hypoperfusion and is the leading symptom of infectious-toxic shock. As a result, the body's attempts to protect itself lead to the development of a vicious circle.

Symptoms of toxic shock syndrome

Symptoms of toxic shock syndrome usually begin with a sudden high fever (body temperature rises above 38°C/100.4°F). Other symptoms then develop quickly, usually within a few hours. These may include:

- vomiting;

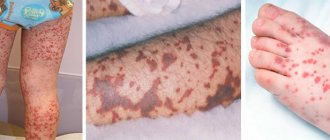

- a sunburn-like skin rash;

- diarrhea;

- fainting or feeling weak;

- muscle pain;

- dizziness;

- confusion.

First signs

Infectious-toxic shock develops against the background of an ongoing illness. However, there are fulminant forms, in which symptoms appear in a short time. Such an example is meningococcal infection complicated by shock. The patient exhibits the following first signs of the development of infectious-toxic shock:

- severe weakness;

- in young children there is a monotonous cry, bulging and tension of the large fontanel;

- severe pain in muscles, various parts of the abdomen, headache;

- indomitable vomiting that does not bring relief;

- rapid spread of rash on the skin of the face, mucous membranes;

- changes in consciousness depending on the stage of shock;

- convulsions;

- frequent shallow breathing;

- arterial hypotension (decreased blood pressure), tachycardia (SI 1.5–2.0);

- increase in body temperature to 39–41 0C or below 36 0C.

Signs may appear in varying degrees. This depends on the patient’s age, his initial condition, the underlying disease, and the treatment performed. For example, the first signs of shock in leptospirosis can be provoked by antibacterial therapy - the bactericidal effect of the drugs causes a massive release of toxins into the blood.

Causes of toxic shock syndrome

Although toxic shock syndrome has been studied for over 20 years, little is known about the syndrome.

The bacteria involved in the syndrome, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes, can be found on the skin and nose in approximately 20-30% of all people. They usually do not cause serious problems.

Most people have toxin-fighting proteins known as antibodies, which can protect the body from these toxins. However, for unknown reasons, a small percentage of people do not produce these specific antibodies.

It is known that bacteria can enter the body through a wound, burn, throat or vagina. They release toxins into the bloodstream, and these toxins interfere with the processes that regulate blood pressure, causing it to drop to dangerously low levels. The bacteria also attack tissues, including skin, muscles and organs.

The kidneys are especially vulnerable to toxins because they filter waste from the blood. Kidney failure is a common complication of untreated toxic shock syndrome.

Tampons

The role of tampons remains unexplained. One theory is that if a tampon is left in the vagina for a while, as is often the case with more absorbent tampons, it can become a breeding ground for bacteria.

Another theory is that tampon fibers can scratch the vagina, allowing bacteria or toxins to enter the bloodstream.

However, no evidence was found to support either theory.

Consequences

The pathogenesis of infectious-toxic shock is based on the development of multiple organ failure. Intensive therapy includes potent drugs that have side effects. Therefore, even with effective treatment, the following consequences are possible:

- gastrointestinal bleeding;

- encephalopathy, apallic syndrome - complete loss of cognitive functions of the brain while maintaining the main autonomic functions;

- secondary infection;

- formation of bedsores;

- polyneuropathy - damage to the peripheral nervous system;

- dysbacteriosis;

- chronic diseases of the liver, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract;

- hearing and vision impairments.

Against the background of increasing cardiac and vascular failure, circulatory arrest may occur. Timely contact with medical specialists will help to avoid irreversible consequences.

Infectious-toxic shock is a complication of diseases caused by microorganisms. The presence of their toxins in the blood activates the defense mechanisms of the immune system. But the reaction extends beyond the boundaries of one organ or system, and therefore a condition develops that threatens human life. Intensive therapy of infectious-toxic shock is possible only in a specialized department. How quickly the victim gets to the hospital will affect not only the further prognosis of the disease, but also the preservation of life.

Infectious-toxic shock

0

Treatment of toxic shock syndrome

There are two important goals in treating toxic shock syndrome:

- infection control;

- supportive care for any body functions that are affected.

The patient must be urgently admitted to the hospital, where he may require treatment in the intensive care unit.

Most people will respond to treatment within a couple of days, but it may take several weeks before people are well enough to leave the hospital.

Treatment of infection

The infection can usually be treated with a combination of antibiotics given directly into the bloodstream through an IV (intravenous) line.

In some cases, immunoglobulin may also be given as an antibiotic. Immunoglobulin is a sample of donated human blood that is known to contain high levels of antibodies that can be used to fight toxins produced by bacteria.

Maintenance therapy

To support breathing, the patient is given an oxygen cylinder. Fluids are given intravenously to increase blood pressure. Fluids also help prevent dehydration and organ damage.

Dialysis

If the kidneys stop functioning, a dialysis machine is used to filter the blood.

Cleaning infected tissue

If toxins have damaged parts of the skin or other extremities of the body, such as fingers or toes, the infected tissue must be drained and cleaned. In very severe cases, surgical removal of parts of the skin or amputation (i.e. surgical removal) of limbs of the body may be required.

Prevention of toxic shock syndrome

Preventing Infection

Prompt and thorough treatment of body wounds can help prevent infection and any risk of toxic shock syndrome.

Care when using tampons

The relationship between TSS and tampon use is unclear, but research suggests that tampon use may be a factor. For this reason, it is important that a woman:

- always used a tampon with the lowest absorbency suitable for the menstrual cycle;

- alternated tampons with a sanitary towel or pads throughout the period.

You must also:

- wash your hands before and after inserting a tampon;

- change tampons regularly - as often as indicated on the packaging;

- never insert more than one tampon at a time;

- When using one at night, insert a fresh tampon before going to bed and remove it after waking up;

- remove the tampon at the end of menstruation.

Complications

Toxic shock syndrome is a life-threatening health condition. In some cases, toxic shock syndrome can affect major organs in the body. If left untreated, complications associated with this disease include:

- liver failure (liver failure);

- renal failure;

- heart failure;

- shock or decreased blood flow throughout the body.

Signs of liver failure may include:

- yellowing of the skin and eyeballs (jaundice);

- pain in the upper abdomen;

- difficulty concentrating;

- nausea;

- vomiting;

- confusion;

- drowsiness.

Signs of kidney failure may include:

- fatigue;

- weakness;

- nausea and vomiting;

- muscle cramps;

- hiccups;

- constant itching;

- chest pain;

- shortness of breath;

- high blood pressure;

- sleep problems;

- swelling in the legs and ankles;

- problems with urination.

Signs of heart failure may include:

- rapid heartbeat (tachycardia);

- chest pain;

- lack of appetite;

- inability to concentrate;

- fatigue;

- shortness of breath (shortness of breath).

Stages

There are several approaches to classifying infectious-toxic shock. Regardless of the etiological factor (reasons), the following stages of development are possible in its course.

Classification of infectious-toxic shock by stages RM Hardaway (1963)

| Reversible shock stage | Irreversible shock stage | ||

| Phases of reversible shock | There is no consciousness. Breathing is grossly impaired. The pulse in the peripheral artery is not detected. Symptoms of DIC syndrome. | ||

| Early | Late | Sustainable | |

| Not always diagnosed. The patient complains of chills, muscle pain, and thirst. There is anxiety, motor agitation, and inadequate assessment of the severity of one’s own condition. On examination, the skin is pale, less often pink, warm to the touch, and may be slightly moist. Blood pressure (BP) does not decrease or even increases slightly. Pulse is frequent. Breathing is rapid. Diuresis (urine output) is reduced. | The person becomes lethargic, indifferent, lies with his eyes closed, and does not want to make contact. The pallor of the skin increases, a “marble” pattern appears, blueness of the tip of the nose, lips, ears, and terminal phalanges of the fingers appears. The skin becomes cold and damp to the touch. There is a gradual decrease in blood pressure and an increase in heart rate (tachycardia). Shortness of breath increases. Body temperature drops to subfebrile or normal. A rash may appear on the skin. | Consciousness is depressed to the point of coma. The skin is bluish. Breathing is shallow with a frequency of more than 30 breaths per minute, irregular. Tachycardia increases, blood pressure is reduced (difficulties may arise in determining it). There is no diuresis. Body temperature is below normal values. Signs of DIC syndrome (blockage of tissue microcirculation with subsequent blood clotting disorders). | |

The clinical classification of degrees of shock by V.I. Pokrovsky et al. (1976) and V.G. Chaitsev (1982) characterizes infectious-toxic shock during meningococcal infection.

The main criterion of severity is the Algover index. This is the relationship between heart rate and systolic blood pressure. It reflects the degree of disruption of microcirculation in organs, in accordance with the depth of shock.

Hence another name - shock index (SI). Normally, this figure is about 0.5. During shock, it increases:

- I degree - up to 1.0;

- II degree - from 1.0 to 1.5;

- III degree - over 1.5.

The shock index is used in conjunction with clinical signs. The symptoms are not always so pronounced that it is possible to distinguish one phase from another. When observing a patient, it is important to notice the dynamics of his condition.

The concept of sepsis has received a new interpretation in recent years. The critical condition is based on systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) - the body’s response to the action of aggressive factors, such as surgery, trauma, and an infectious process. Sepsis is a syndrome of systemic inflammatory response to the introduction of pathogenic microorganisms into the body. Therefore, some authors draw an analogy between infectious-toxic and septic shock, which received code A 41.9 in ICD-10.